By: Gary Rogers

Crossbreeding in dairy herds continues to increase largely due to increased inbreeding in purebred populations and increased cost of production. Properly designed crossbreeding programs can reduce dairy production costs, increase income, and improve ease of management in modern commercial herds. However, many dairy producers and industry specialists continue to have questions about how to implement crossbreeding in dairy herds and especially about how many breeds to utilize.

Generally, no one crossbreeding system will work best for all herds (or even most) as many factors impact the best approach to crossbreeding in commercial dairy herds.

Basic concepts related to crossbreeding

Crossbreeding relieves inbreeding depression so inbred populations benefit considerably from crossbreeding. Modern dairy populations have significant inbreeding, so crossbreeding will be beneficial in commercial dairy herds. See a recent article on inbreeding and its effects on performance in dairy cattle https://www.norwegianred.com/news/the-important-role-of-norwegian-red-in-crossbreeding/.

Heterosis or hybrid vigor results from the relief of inbreeding depression and heterosis is a key benefit to most crossbreeding programs. Rotation of breeds by using purebred sires has several advantages over using crossbred sires so purebred sires from well-developed breeding programs should be the mainstay of crossbreeding programs in commercial dairy herds.

The bottom line is that properly designed crossbreeding programs will eliminate important concerns over inbreeding and provide some level of heterosis.

More breeds result in more heterosis

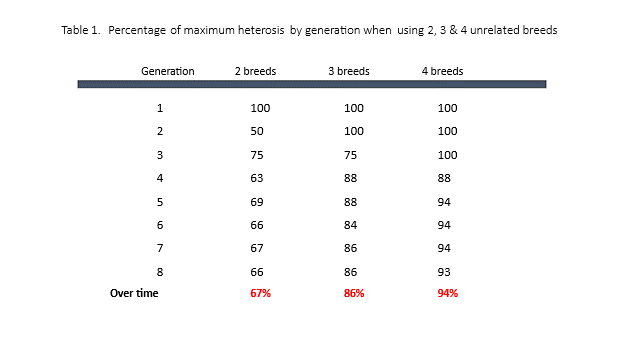

The optimal number of breeds to include in a crossbreeding rotation depends on many factors. The inclusion of more breeds results in more heterosis but maximizing heterosis should not be the overall herd objective. Maximum heterosis in the offspring results when two unrelated breeds or unrelated crossbreds are mated. The percentage of maximum heterosis for each generation of crosses that is expected from 2-breed, 3-breed, and 4-breed rotations is included in Table 1.

The percentage of maximum heterosis over several generations of crossing is 67% for 2 breeds, 86% for 3 breeds, and 94% for 4 breeds so adding more unrelated breeds to a crossbreeding program results in more heterosis but the marginal increase in heterosis by adding more breeds declines with each additional breed.

Note that heterosis is 50% of the maximum in the second generation cross when using a 2-breed rotation and this is the lowest heterosis for any crossbreeding program. In a 2-breed rotation, this second-generation cross is called a backcross. Sometimes this backcross is mistakenly thought to provide no (zero) heterosis by those who are new to crossbreeding. Still, it provides half as much heterosis as the first-generation cross.

Benefits of fewer breeds

Adding breeds to the rotation results in more heterosis but the overall benefit of additional breeds may be smaller than the benefit of choosing a smaller number of breeds. Increased heterosis form an additional breed may not make up for the reduced sire performance from the additional breed especially if the additional breed has a limited breeding population or the additional breed is not economically competitive in the local economic and herd management circumstance. Crossbreeding programs should aim to produce the most profitable and sustainable herd that fits the local economic circumstances and herd management situation. This could involve two or three breeds and perhaps four breeds in rare circumstances.

Two-breed rotations can have advantages over 3-breed rotations and 3-breed rotations can have advantages over 4-breed rotations even though heterosis will be slightly lower when using fewer breeds. For example, in the situation comparing 2-breed rotations with 3-breed rotations, the 2-breed rotation can have better economic performance and be easier to manage in some herd circumstances. This is especially true in herds that need simplicity in mating programs (such as in large herds that use group matings) or that have specific needs for variability and range in cow sizes due to facility design.

Adding breeds always has the potential to result in cows that may not fit facility design and more breeds can add complexity that results in poor mating or breeding program compliance.

Using a smaller number of breeds can also have advantages that more than offset the reduced heterosis due to finding additional breeds that fit the local milk market or beef market well. Adding an additional breed to a 2-breed or 3-breed rotation may not make economic sense for many herds even though it might result in more heterosis.

Sire selection or sire performance within a breed is at least as important as heterosis when deciding the number of breeds to use in a rotation. Breeds with large, well-developed breeding programs will have sires that are more extreme for combinations of key traits, and they will be more likely to have sires that meet local herd economic and herd management requirements. Using very high-merit sires from large, well-developed breeding programs can result in benefits that outweigh the additional heterosis that comes from an additional breed.

The bottom line is that breed contribution and breed merit along with sire merit and sire performance within a breed are both important for deciding the optimal number of breeds to use in a crossbreeding program.

How to choose sires to use in crossbreeding programs

Crossbreeding is not a substitute for using high-merit sires. The use of top sires in a crossbreeding program is as important as using top sires in a purebred breeding program. Crossbreeding should not be used as an excuse to use “average” or “cheap” sires. The use of top sires chosen to meet the needs of the local herd is critical for a successful crossbreeding program. The use of top sires is usually more important than including an additional breed.

Also, the importance of key traits for proper sire selection will depend on economic circumstances as well as herd management requirements. Indexes used to select sires for crossbreeding programs should be based on economic inputs as well as how breeds and sires complement each other.

Norwegian Red in crossbreeding programs

The best use of Norwegian Red sires in a crossbreeding rotation depends on many factors including those mentioned above. Norwegian Red sires have been used very successfully in many 2-breed and 3-breed rotations. Analyses of recent data from several herds illustrate that Norwegian Red sires provide outstanding daughter performance in both 2-breed and 3-breed crossbreeding programs.

The use of Norwegian Red sires and Holstein sires in a 2-breed rotation has been very successful with data available from some large herds that have 4 generations of 2-breed crosses involving Norwegian Red and Holstein. Crossbreds involving these two breeds have milk, fat, and protein yields similar to or higher than pure Holsteins when top sires are selected from each breed. In addition, the 2-breed crosses have improved fertility, lower mortality and culling for health-related problems as well as higher bull calf and cull cow value even though liveweights are lower for the crosses compared to pure Holsteins.

The 2-breed crosses also consume less feed than purebred Holsteins making them more efficient as similar or higher milk energy production with lower feed intake indicates an advantage in feed efficiency.

Norwegian Red sires have also worked well in 3-breed rotations. Many of the successful 3-breed rotations involve Holstein, Norwegian Red, and Jersey but some involve Holstein, Norwegian Red, and either Fleckvieh, Montbeliarde, or Brown Swiss. Crosses with these latter three breeds have been more popular in Europe where the breeds originated and where beef prices have always been relatively high.

A successful 3-breed rotation also requires proper sire selection so that the resulting crossbred performance is in line with the local economic and herd management circumstances. Norwegian Red sires fit almost all local economic and herd management circumstances, so they have made and currently make important contributions to successful 3-breed rotations.

Summary

Crossbreeding in dairy herds continues to increase. High dairy input prices, inbreeding in purebred populations as well as global pressure on dairy industry sustainability will continue to drive growth in crossbreeding in commercial dairy herds.

The optimal number of breeds to use in a crossing program depends on many factors but most herds will find that either a 2-breed rotation or a 3-breed rotation is best for their herd. The 2-breed rotation has some important advantages compared to a 3-breed rotation, but the 3-breed rotation will provide a higher level of heterosis.

Sire selection or sire performance within a breed is at least as important as heterosis when deciding the number of breeds to use in a rotation. Breeds with large, well-developed breeding programs will have sires that are more extreme for combinations of key traits, and they will be more likely to have sires that meet local herd economic and herd management requirements.

Using very high-merit sires from large, well-developed breeding programs can result in benefits that outweigh the additional heterosis that comes from an additional breed. Herd owners and managers should always properly weigh the benefit of slightly higher heterosis versus the benefits of using fewer breeds.

Norwegian Red sires are a perfect component of crossbreeding programs because they provide extreme daughter fertility and health performance along with outstanding milk, fat, and protein yields. In addition, Norwegian Red sires produce slightly smaller, more efficient cows with substantially improved beef performance when used in a crossbreeding program with Holsteins.